ARTICLE AD BOX

Lucy WilliamsonMiddle East correspondent, Hebron

Reuters

Reuters

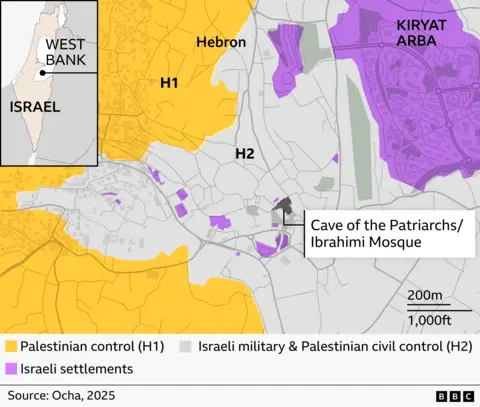

About 800 Jewish settlers live among 33,000 Palestinians in the H2 area of Hebron

A Palestinian official in the occupied West Bank has described Israel's latest expansion of control there as "the end of the road" for negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians.

Asma al-Sharabati, acting mayor of Hebron, said new legal changes recently announced by Israeli cabinet ministers would leave Palestinian authorities shut out of decisions on urban planning and development, even in areas under Palestinian control.

Hebron is a regular flashpoint in the West Bank - a divided city, where soldiers guard hundreds of Israeli settlers living alongside Palestinians in an Israeli military garrison.

On Sunday, the Israeli security cabinet passed major changes to the established division of powers in the West Bank, set up three decades ago under the US-backed Oslo Accords, signed by both Israeli and Palestinian leaders.

They include expanding Israeli control beyond its military occupation, into the provision of municipal services in Palestinian-run areas, as well as broad powers to take over so-called "heritage sites" across the West Bank – to protect water, environmental and archaeological resources, they say.

Israel also says it will take over planning authority at the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron, one of the holiest sites in Judaism, which sits inside the city's Ibrahimi Mosque.

"Now they can simply put their hands on any building and declare it is ancient, and the Palestinian authorities are not part of any decision on urban planning or development of the area," said al-Sharabati.

She told us she had not received any formal notification of Israel's plans, and was picking up the details from Israeli news.

A few metres from Hebron's bustling vegetable market, through the grey steel gates of the Israeli checkpoint, is a tense and deserted landscape, where Palestinian shops are shuttered, and streets closed off to protect Israeli settlers.

Asma al-Sharabati says international institutions are not protecting Palestinians

Issa Amro, a Palestinian activist, lives inside that volatile divided area, known as H2. The long and winding route to his house takes us through the back gardens of Palestinian homes, and along stony pathways, to a hill overlooking the neighbourhood.

When we arrive, an ultra-Orthodox Jewish couple are picnicking under the trees outside. A local settler appears from a neighbouring house and follows us a little way down the path.

Inside Issa's house, a plaque reads "Free Palestine". Through his window, a vast Israeli flag can be seen fluttering over the streets below.

He points out the Palestinian buildings nearby, emptied of residents after years of tension and expanding Israeli control.

But Issa says these new changes are different.

"They were expanding a lot without any legal basis," he said. "Now they [will be] the law. They are changing the status from Occupied Territories to a legal dispute. It's part of Israel now without any rights for me. It's annexation of the land without me, as a Palestinian."

Issa Amro says many of his neighbours have left

Israel plans to start providing municipal services to Jewish settlers in Hebron, and open up land ownership across the West Bank to private Israeli citizens. Palestinians are banned from selling property to non-Palestinians under both Jordanian and Palestinian law.

Some of those who sold covertly to Israelis in the past now face real risks from Israel's planned publication of classified land registry there.

The social taboo of selling to the Israeli occupier runs deep.

Jibril Moragh lives next to Hebron's Ibrahimi Mosque. He told me that he had refused an offer from a group of Israelis to buy his house 18 years ago.

"One of them offered me 25 million shekels [$8m], but I refused," Jibril told me. "The man said he would pay whatever I wanted, and that I could keep living here for as long as I liked. But you don't sell to the occupation [Israel]."

More than 700,000 Israeli settlers live in the occupied West Bank and Israeli-annexed East Jerusalem, territories captured by Israel from Jordan in the 1967 Middle East War. Those lands are wanted by Palestinians for their hoped-for independent state along with the Gaza Strip.

The settlements are illegal under international law.

'Burying' Palestinian statehood

The opening up of property rights, and the sweeping transfer of civilian powers in Palestinian-run areas, marks a significant shift in Israel's long expansion of control over the West Bank, which has escalated after the 7 October 2023 Hamas attacks on Israel, and the war in Gaza.

"We are deepening our roots in all parts of the land of Israel," said Finance Minister, Bezalel Smotrich, who has responsibility for settlement policies, when he announced the new measures. "And burying the idea of a Palestinian state."

"Judea and Samaria is the Jewish homeland of the people of Israel," said Zvi Sukkot, a lawmaker in Smotrich's far-right Religious Zionism party. "I expect there to be full Israeli sovereignty here, but in the meantime at least we can supervise, so there will be no environmental harm, and we won't harm the heritage of the people of Israel, even if it's in Palestinian-run areas."

But these latest legal changes not only demolish the agreements Israel signed decades ago, they also drive a hole through the remaining powers of the Palestinian Authority, which has been earmarked in Donald Trump's peace plan to eventually take over power from Hamas.

Reuters

Reuters

A street in Hebron's Old City is covered by netting to stop stones thrown by settlers onto merchants and passers-by

"We are living the ugly truth that we are not protected," said Hebron mayor, al-Sharabati. "Institutions are not protecting us. And the world is seeing the Gaza Strip and the massacres, and talking about them, but no more than that."

Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas has called for a "firm response" from the US government, saying Israel's decision disrupts Donald Trump's efforts in the region and violates international law.

So far, President Trump has said little beyond reiterating his opposition to Israel's formal annexation of the West Bank.

Several countries, including the UK, last year recognised a Palestinian State. Now that Israel has given itself civilian powers in Palestinian-controlled territory, we asked the UK government what it would do in response.

Hamish Falconer, the Under-Secretary of State for the Middle East, told us that people could expect to hear more from the UK government in the coming days.

"We strongly condemn the decision and expect to see it reversed," he said. "Almost all of Israel's friends are saying this is a terrible, terrible mistake."

Reuters

Reuters

The Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron, also known as the Ibrahimi Mosque, is the second holiest site in Judaism and the fourth in Islam

The expansion of Israeli presence and control across the West Bank has continued while international focus remains on Gaza.

But Trump's plan for Gaza depends on the support of Arab countries, many of whom are demanding progress towards a Palestinian state.

What happens in Hebron – and the rest of the West Bank - could still threaten Trump's vision for Gaza, and his plan for wider Middle East peace.

Additional reporting by Yousef Shomali & Rebecca Hartmann

1 hour ago

3

1 hour ago

3

English (US) ·

English (US) ·